Introduction

What are mandrels and what are they used for?

Mandrels for In‑Mould Labelling (IML) are complex and precise mechanical, pneumatic, and electrical tools. They are the single most important component responsible for the quality of the in‑mould labelling process.

Their purpose is to pick up the IML label from the label feeder, form the label to the required shape, and then safely transport the prepared label into the cavity of the injection mould. Inside the mould cavity, the mandrel applies an electrostatic charge to the label and places it onto the metal surface of the mould.

Mandrels are a key element of the IML process and largely determine whether the entire process is successful. They are custom parts, designed each time for a specific application and a specific label geometry. In general, the mandrel’s shape is a reflection of the injection mould cavity and the IML label geometry.

How does electrostatic charging of IML labels work?

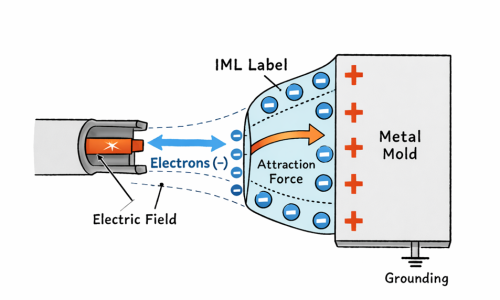

Applying high voltage to the mandrel releases electrostatic charge (electrons) from the active element (a copper tape or plate, or a copper or titanium pin). The released electrons then follow the shortest possible path towards ground (the injection mould), encountering an insulator on the way (the IML label). The charge accumulates on the surface of the label, generating a strong electrostatic field that attracts the label to the grounded mould (so‑called Coulomb attraction).

The attractive force must balance both gravity and the forces resulting from internal stresses in the label that tend to ‘flatten’ it. In addition, it must keep the label in place during the injection of molten polymer into the mould. This is a simplified and visual description, but it is sufficient to understand ‘how it works’ at a basic level.

Construction of mandrels for IML technology

Types of mandrels

There are three basic types of mandrels used in IML technology:

Foam mandrels

Foam has dissipative properties. It enables effective transfer of electrostatic charge to the label, while also exhibiting high resistance, which reduces the risk of sudden arc discharges (sparking) upon contact with the mould.

In simplified terms, such a mandrel consists of three layers: a load‑bearing base (typically PA 6.6 or PP), a copper foil or thin copper plate in the label area connected to the high‑voltage source, and an outer layer of suitable foam (available, for example, from Simco).

This solution has been used for many years and has several advantages.

Advantages:

- the simplest mandrel design,

- the foam can compensate for minor positioning errors—useful in older applications, on worn/less precise robots or injection moulding machines,

- cost‑effective,

- easy to repair.

Disadvantages:

- the foam wears easily, requiring frequent repairs,

- the foam’s dissipative properties change over time (due to contamination and moisture), reducing long‑term process stability (scrap may increase without obvious mandrel‑related causes),

- the label is typically held on the mandrel by suction cups, which can wrinkle the label and does not always ensure precise placement in the mould cavity,

- limited use of higher charging voltage (typically up to 12 kV), which results in weaker label charging; this matters in high‑speed and thin‑wall applications where the high injection speed can shift the label; increasing voltage may ‘burn’ the foam and cause an electrostatic discharge between the mandrel and the mould,

- lower charging voltage often requires longer charging time in the mould, increasing overall production time,

- a major drawback is foam crumbling during operation, which can contaminate finished parts with foam particles.

Summary:

This technology is rarely used for new mandrels today. It still has applications, particularly in long‑cycle, low‑volume processes and where the overall Robot–EOAT–Mould–Injection Moulding Machine stiffness is low (high vibration) and vibration compensation via foam is required.

Below is an example photo of a foam mandrel.

Resin mandrels

Resin mandrels are conceptually similar to foam mandrels, except that the foam is replaced with a resin with dissipative properties. The design is comparable and also consists of three layers: a base (typically PA 6.6 or PP), a copper plate or copper tape, and resin.

Resin (e.g., EasyCore by Simco) requires experience to apply. It is supplied as a two‑component mixture (resin + hardener) that must be thoroughly mixed immediately before application. This is a critical step; improper mixing leads to many application problems.

Another important step is casting the resin onto the mandrel. Before curing, the resin is a high‑viscosity liquid. Typically, the mandrel is designed with additional walls that limit the resin only to the required areas. It is essential that the resin fills the intended volumes well and that these volumes are properly vented.

A common issue during resin application is air bubbles (air pockets) trapped either within the resin (air did not escape in time) or at the interface between the resin and the base material (where resin ‘captures’ air). Air pockets significantly change the resin’s electrical characteristics. This is critical in multi‑cavity applications: the difference between the ‘best’ and the ‘worst’ mandrel may be large enough that it becomes impossible to set universal process parameters for all mandrels.

Advantages:

- no crumbling effect,

- long service life,

- very good, uniform electrostatic charge distribution on the IML label,

- suitable for high‑speed applications.

Disadvantages:

- the most expensive solution, considering the complex resin application and curing process,

- no repair option—damage to the resin surface typically means the entire mandrel must be replaced,

- requires frequent cleaning, as contaminants on the resin surface affect its properties, including a ‘sticking’ effect where the label adheres to the mandrel.

Summary:

This is the most advanced and therefore the most expensive technology. However, when correctly manufactured and properly maintained, resin mandrels deliver the highest in‑mould labelling quality. They tolerate many label imperfections and perform exceptionally well with labels featuring high surface resistivity. Mandrels made with this technology are commonly produced for demanding applications, high‑volume multi‑cavity production, often using stacked moulds. It is worth noting that resin mandrels can be manufactured effectively only by an experienced company with the right tooling and a refined process.

Below is an example photo of a resin mandrel.

Pin mandrels

Pin mandrels are based on a slightly different principle than the solutions described above. There is no copper tape; instead, they use sharpened pins made of copper or titanium. Applying high voltage to a pin causes electron emission from its sharpened tip.

The design of a pin mandrel is more complex than a foam mandrel, but simpler than a resin mandrel. Pins should be mounted at least 10 mm from the label surface; the mounting angle relative to the label is not critical. Charges are always emitted from the sharp tip and follow the shortest path to ground.

Charges emitted from pins spread in a cone shape and charge the label locally—closest to the pins. As a result, the label is not charged uniformly over its entire surface; ‘islands’ of higher potential appear. If the label’s surface resistivity is appropriate, charges spread across the label and become more uniform. Local charging is generally not an issue during injection, provided that pin placement targets the critical areas that most influence correct label application.

A major advantage of pin mandrels is significantly lower weight compared to foam and resin mandrels—often up to 50% less. They are typically designed as a lattice structure with large open areas. The insulator and charge‑transfer medium is air. These mandrels do not require special cleaning and are highly durable and stable; they do not wear in normal operation. In practice, they are replaced only if mechanically damaged.

Advantages:

- significantly lower cost than the resin solution,

- lower weight,

- repairable,

- stable over very long periods of use,

- no special handling required (e.g., periodic cleaning),

- suitable for very short cycles and multi‑cavity moulds, including stacked moulds,

- repeatable manufacturing parameters can be maintained easily, translating into consistent performance of all mandrels for a given application,

- no crumbling.

Disadvantages:

- requires that the designer understands the label charging process in order to position pins correctly,

- non‑uniform (local) charging of the IML label,

- because the mandrel is rigid, it cannot compensate for robot positioning imperfections or damp vibrations.

Summary:

This type of mandrel is currently the most popular. It is relatively simple and maintains stable electrical properties over long periods. It is a strong alternative to resin mandrels. High charging voltages can be used (even above 18 kV), which significantly shortens charging time in the mould and reduces total cycle time. Diagnostics are also straightforward, as all pins are easily accessible and their conductivity can be checked easily.

Below is an example photo of a pin mandrel.

Hybrid mandrels

Used in specific applications or process conditions. They combine the advantages (and sometimes disadvantages) of different mandrel technologies. The use of hybrid mandrels should be well considered, and the need should clearly result from the application conditions.

Materials used for mandrels

Conventional materials

The base material most commonly used for mandrels is PP. This is due to its mechanical and electrical properties and its low density (approx. 0.9 g/cm³), which enables lightweight designs. Unfortunately, PP also has a major drawback: it is chemically inert and has low surface energy, which significantly complicates bonding copper or foam. In addition, it has a relatively high tendency to creep (dimensional change under long‑term load) and is relatively expensive.

PA 6.6 is also commonly used. It avoids the drawbacks above, but has higher density and is hygroscopic, tending to absorb moisture over time, which negatively affects long‑term process stability. Other materials used include ABS, PA 6 (cost‑effective), or PET (much more expensive and stiffer).

3D printing

The vast majority of mandrels produced today are manufactured using additive methods. When selecting a printing material, it is worth comparing its mechanical and electrical properties to baseline PP or PA 6.6. Mandrels are produced using FDM (ABS, PET, PP), SLS (PP, PA12), or, much less frequently, SLA (a PP equivalent). The most common technologies today are FDM and SLS.

Note that with sintered powder printing technologies, mandrels must be additionally sealed with dedicated adhesives, as they are not airtight by nature and allow air permeability.

Additive manufacturing can reduce mandrel preparation cost by 30% to 50% compared to traditional subtractive methods (machining). While the structural strength of printed mandrels is lower than that of machined mandrels, it is sufficient for most applications.

How to take care of mandrels

Mandrels must be clean and dry

It is best to handle a mandrel only when wearing clean, white gloves.

Contaminating a mandrel, for example with oil, may—depending on the manufacturing technology and mandrel type—disqualify it from further use.

Mandrels are delicate (and very expensive)

All assembly, disassembly, and mould positioning activities should be performed slowly and carefully, maintaining cleanliness at the workplace. It is strongly recommended to prepare a clean work area in advance where the mandrel and tools can be placed.

Mandrels are often damaged when an operator removes the mandrel from the robot arm and turns around with it in their hand, looking for a place to put it down.

Mandrels are sensitive to ambient conditions

Proper storage conditions are essential. Mandrels should not be stored in damp, dirty, or hard‑to‑access locations. Each mandrel should have a dedicated storage place for periods when it is not needed.

It is good practice to wrap mandrels in bubble wrap and store them in a dedicated, dry, and clean room. If mandrels are made of PP, ensure they are not stored in a position that may cause deformation—especially if stored for a long time.

Cleaning mandrels

On the robot arm, mandrels can be gently cleaned with a slightly damp, lint‑free, clean cloth. Wait a few minutes before starting to ensure they are fully dry.

After removing mandrels from the robot arm, they can also be cleaned with a damp, lint‑free, clean cloth. For resin mandrels, deionized water can be used to improve cleaning effectiveness.

Do not clean foam mandrels with water—water will not evaporate from the foam. They can be blown off with compressed air (clean and dry), while keeping a safe distance between the air gun and the mandrel.

Pin mandrels are the least sensitive—very little can harm them.

In general, no additional agents or solvents are used for mandrel cleaning.

Resin mandrels require the shortest cleaning interval. They should be cleaned regularly, as contaminants can accumulate on the resin surface and change mandrel properties. Pin mandrels are cleaned least frequently—typically only during disassembly before storage.

What to check on mandrels

After disassembly and cleaning, and before reassembly, it is worth checking:

- the durability and stiffness of mechanical joints (all screws, rods, threads)—by hand, without tools,

- airtightness—verify that pneumatic fittings/connectors are tight, especially important for vacuum,

- the condition of high‑voltage (HV) cables—no abrasion, kinks, or loose terminals,

- conductivity—for pin mandrels, check continuity (short circuit) between all pins and the HV lead or HV connector,

- the general condition of the mandrel.

Typical IML process using mandrels

Typical process algorithm

- The robot arm with mandrels moves to the IML label feeder (label magazine).

- Labels are transferred to the mandrels. Vacuum is enabled on the mandrels and the labels are drawn in and held by negative pressure.

- The robot arm with mandrels and labels moves to the injection mould.

- At a distance of approximately 0.5 mm between the label on the mandrel and the injection mould, the high‑voltage generator is enabled, charging the label electrostatically. Charging lasts from 100 ms up to approximately 1 second (depending on mandrel type, charging voltage, label type, etc.). This value is most often determined experimentally.

- After charging is complete, vacuum is switched off and blow‑off is enabled on the mandrel. The label jumps onto the cavity surface.

- With blow‑off still enabled, the mandrel is withdrawn from the mould, leaving the label in the mould. Once the mandrel is out of the cavity, blow‑off can be switched off.

- The cycle starts again.

Possible deviations

There are many possible variants of the above algorithm. It should be treated as a baseline that can be modified and optimized depending on the application. For example:

Hard‑to‑charge labels

It can be beneficial not to switch off charging after step 4. Instead, transfer the label to the cavity surface and, with charging still enabled, withdraw the mandrel to roughly 1/3 of its height—then switch off charging.

Easy‑to‑charge labels and self‑positioning applications

In this variant, label charging can be enabled before entering the injection mould and maintained while inserting the mandrel into the mould. No dwell time in the mould is needed; immediately after insertion, vacuum is switched off, blow‑off is enabled, charging is switched off, and the mandrel is withdrawn from the mould cavity. This approach saves in‑mould charging time and reduces the overall production cycle.

Typical application problems

Here we assume that the application is mature—everything worked before—and now, for some reason, it no longer works. Key causes include:

Labels

Incorrect label quality accounts for a significant share of application problems. To diagnose this, use labels from the previous production batch. If problems disappear, focus on the labels. Labels should always be conditioned in the production hall for at least 24 hours before the planned production start.

Mandrels

Among mandrel‑related issues, the most common are:

• incorrect mandrel positioning in the injection mould,

• incorrect label feeder positioning relative to the mandrels,

• no electrostatics (damaged high‑voltage cable) or electrical breakdown on the mandrel or HV cable,

• insufficient label wrapping on the mandrel due to vacuum leakage (most often at fittings/connectors),

• dirty or clogged vacuum channels or suction cups,

• no blow‑off on the mandrel,

• contaminated foam mandrels,

• contaminated or sticky resin mandrels.

Injection mould

Insufficient mould cooling. The injection mould temperature during IML label application should not exceed 35°C. If flash‑related issues occur, check whether the cavity surface is too hot.

Atmospheric conditions

If the production hall atmosphere is not controllable and monitored, significant issues may occur in IML label applications. Exceptionally high ambient temperatures (e.g., hot and sunny days) may drive a sharp increase in humidity. High humidity changes the electrostatic conditions of mandrels, labels, and the injection mould.

Any parameter changes made under such conditions should be treated as temporary, so that when atmospheric conditions normalize, the process can be returned to the baseline settings.

Summary

Mandrels for IML technology are the most complex single tool that must be custom‑built for each application. Their high price results from the required design work, high manufacturing precision, and the time‑consuming assembly process. All of these steps are performed as one‑off work for a given mandrel set and cannot reasonably be automated (not yet). Differences between mandrel types and manufacturing quality translate directly into production stability, cycle time, and scrap rates related to IML.

This is not the only element responsible for IML process quality, but it is a key one. Proper selection of mandrel technology, manufacturing method, and material is essential to maintain high process repeatability.

About MATSIM

What we do

MATSIM specialises in designing and building IML equipment, robots, and tooling—including mandrels. We build both simple sub‑stations for feeding single labels and advanced, robotised production cells with side‑entry robots. We integrate our solutions with third‑party products—injection moulding machines, Cartesian robots, safety guarding, and more.

MATSIM in numbers

As of 2025:

• 16 people, with an in‑house tool shop and design office,

• we design and manufacture more than 100 mandrels per year,

• our mandrels are operating in companies in Poland, the Czech Republic, Spain, and the United States,

• MATSIM manufactures and supplies around 30 different types of injection‑moulding automation equipment per year, including: handle inserters, IML label feeders (magazines), lid closers, vision inspection systems, stackers, and more,

• the IML engineering experience within MATSIM exceeds 20 years.

How we can help

We have broad expertise in injection moulding technologies. We support our customers throughout all phases of implementing and maintaining IML technology—both on the equipment side and the process side. We advise on solutions, support the selection of third‑party equipment, verify technical parameters of selected equipment, and help stabilise production processes.IML Technology Guide